VOLUME 11 NUMBER 1 (January to June 2018)

Philipp. Sci. Lett. 2018 11 (1) 022-029

available online: April 24, 2018

*Corresponding author

Email Address: mudjiesantos@gmail.com

Date Received: November 10, 2017

Date Revised: April 30, 2018

Date Accepted: May 17, 2018

ARTICLE

Not fish in fish balls: fraud in some processed seafood products detected by using DNA barcoding

by Katreena P. Sarmiento1,2, Jacqueline Marjorie R. Pereda1, Minerva Fatimae H. Ventolero1, and Mudjekeewis D. Santos1,*

1Genetic Fingerprinting Laboratory, National Fisheries Research and

Development Institute, 101 Mother Ignacia Ave., South Triangle, Quezon City,

Metro Manila, Philippines, 1103

2Department of Biology, School of Science and Engineering,

Ateneo de Manila, Metro Manila, Philippines, 1108

Development Institute, 101 Mother Ignacia Ave., South Triangle, Quezon City,

Metro Manila, Philippines, 1103

2Department of Biology, School of Science and Engineering,

Ateneo de Manila, Metro Manila, Philippines, 1108

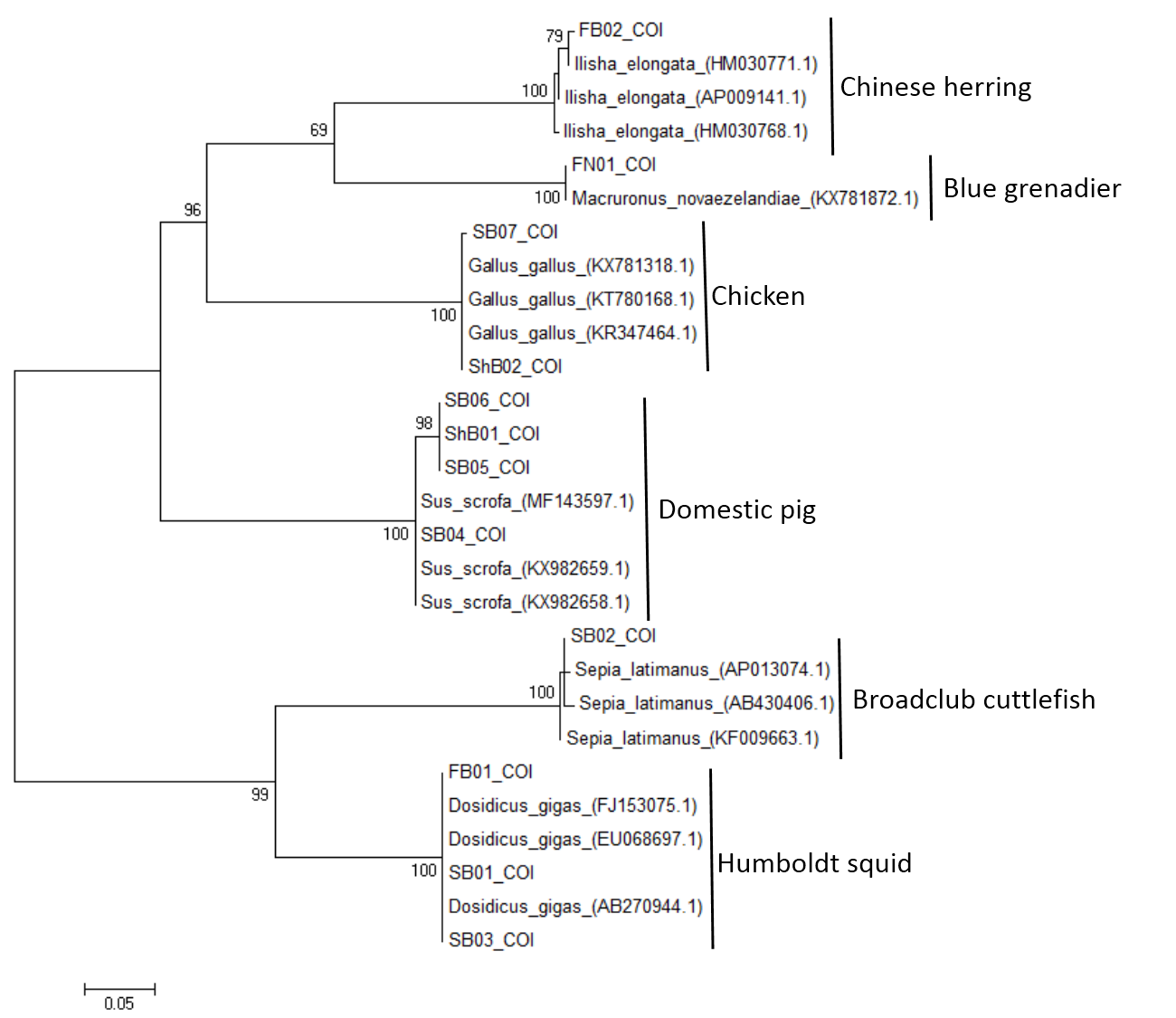

One of the most popular processed seafood products in the Southeast Asian region, “fishball” is a round, white food containing fish meat and other ingredients such as salt, starch, and sugar cooked in oil and sold as street food. Fish products are among the leading food categories with reported cases of food fraud— fish samples purchased at grocery stores, restaurants, and sushi bars are mislabeled. Fishballs are anecdotally known as being made up of shark meat. To identify the animal species used in commercially processed seafood products, we utilized DNA barcoding by analyzing cytochrome c oxidase I gene, which was further validated by cytochrome b gene. Twelve seafood products, including fish balls, fish nuggets, squid balls, and shrimp balls, were collected from supermarkets, street vendors, and commercial stalls in Iloilo City, Marikina City, and Quezon City, Philippines. Results revealed that processed seafood products manufactured and/or sold by well-established companies conform to some extent with their respective labels: fish balls contained meat from Chinese herring, Ilisha elongata, and broad club cuttlefish, Sepia latimanus; fish nuggets were composed of blue grenadier, Macruronus novaezelandiae; squid balls came from Humboldt squid Dosidicus gigas. Products sold by unknown companies or those with no labels—the products sold mostly as street food—showed an entirely different composition. Samples labeled squid and shrimp ball came from domestic pig, Sus scrofa, and chicken, Gallus gallus, suggesting that some seafood products being sold are mislabeled and misdeclared. We highlight the need for increasing quality control and inspection on lesser-known processed seafood product sources for consumer welfare and safety. DNA barcoding is an effective tool in assessing food identity and traceability in commercial fishery products even for those already processed.

© 2026 SciEnggJ

Philippine-American Academy of Science and Engineering